Berlin is a city shaped by history, division, and secrecy. For this reason, it is no coincidence that the Berlin Spy Museum is located here. This space allows visitors to enter the clandestine world of spies, secret agents, and covert operations. More than a museum, it is a gateway into a reality that operated in the shadows for decades.

Located in the heart of the city, the Berlin Spy Museum stands as a testament to Berlin’s central role in the history of international espionage. From the very first rooms, one thing becomes clear. Espionage is not only a phenomenon of the past. Rather, it is a practice that has evolved alongside technology, politics, and global conflict.

Berlin Spy Museum: A Journey Through Time and Secrecy

The Berlin Spy Museum opened its doors in September 2015. It was founded by Franz-Michael Günther, a former German journalist. However, the project did not emerge overnight. In fact, it took more than ten years to become reality.

During that time, Günther reflected deeply on espionage. This was not an abstract subject for him. It was a lived experience.

During the communist period, he had confrontations with the East German Stasi. The Ministerium für Staatssicherheit—better known as the Stasi—was one of the most extensive and invasive intelligence services in the world. Its reach extended into every layer of East German society.

The Stasi relied on a vast network of informants. Neighbors, colleagues, friends, and even family members were recruited to observe and report. So, private life was rarely private.

As a journalist, Günther experienced this system from close range. This means he witnessed how surveillance, intimidation, and psychological pressure were used to control information and silence dissent.

Files were built in secret. Lives were monitored in detail. Trust itself became fragile.

These encounters left a lasting mark. They revealed how espionage was not only about foreign enemies, but also about controlling one’s own population. Information became power. Fear became a method.

From this perspective, Günther made a decisive choice. He set out to create a museum dedicated exclusively to the history of espionage in Berlin. Not as spectacle alone, but as documentation and reflection.

From that decision, an exhibition was born. It spans from the earliest methods of secret communication to today’s sophisticated intelligence technologies. In doing so, it places the Stasi alongside other intelligence agencies within a broader historical framework.

In addition, the museum combines rare historical objects with high-tech multimedia installations. Because of this balance, the exhibition quickly attracted public attention. Soon after, it received recognition from international media, surprised by its innovative and critical approach.

An Immersive Experience from the First Step

From the moment visitors enter the Berlin Spy Museum, they are immersed in a carefully constructed atmosphere. Overhead cameras, ambient sounds, and interactive screens create a constant sense of surveillance.

Next, the route leads to the Zeittunnel, or Time Tunnel. This symbolic transition prepares visitors to enter the history of espionage.

The tunnel opens into the museum’s main exhibition space. Altogether, it extends over more than 3,000 square meters.

At this point, the narrative structure becomes evident. Each room flows into the next.

From here, a journey begins that blends the digital with the material.

On one hand, espionage history unfolds through original objects and documents. On the other hand, recreations, projections, and audiovisual resources provide context.

Importantly, everything is designed to be accessible. Even visitors with no prior knowledge can follow the story with ease.

Moreover, the interactive nature of the Berlin Spy Museum encourages active participation.

Visitors not only observe. They explore, decode, and question.

This approach turns the visit into a dynamic learning experience. Understanding emerges intuitively.

Currently, the collection includes more than 1,000 carefully curated items. Among them are hidden listening devices, encryption tools, disguised weapons, and surveillance equipment.

Together, these objects impress through their design. At the same time, they reveal the strategies, risks, and tensions that defined espionage throughout history.

One of the most significant takeaways from the museum, however, comes at the end of the journey.

As visitors reach the final floor, it becomes clear how deeply surveillance has changed over time.

Here, historical espionage gives way to contemporary realities. Current conflict zones, digital monitoring, cyberwarfare, and global intelligence operations come into focus.

In this final section, the museum makes a powerful statement: the world of espionage is not confined to the past.

Instead, it remains very much alive—sustained by present-day conflicts, technological acceleration, and a persistent sense of global unease.

A Private Museum in a Symbolic Location

During the Cold War, Berlin was not only divided politically. It was fractured spatially. Streets ended abruptly. Squares disappeared behind concrete and barbed wire. Leipziger Platz, once one of the city’s most vibrant urban centers, became a void.

Before the Second World War, Leipziger Platz was a lively hub of commerce and culture, surrounded by cafés, department stores, and constant movement. However, after 1961, with the construction of the Berlin Wall, the square lost its function entirely. It was absorbed into the border regime and erased from everyday life.

Leipziger Platz lay directly within the “death strip,” the heavily fortified zone separating East and West Berlin. Guard towers, floodlights, patrols, and anti-escape measures transformed the area into a landscape of fear and control. Civilian access was impossible. What had once been a place of encounter became a space defined by absence.

This transformation made Leipziger Platz a silent witness to the Cold War’s logic. It embodied the idea that territory itself could be weaponized. Urban space was no longer neutral; it was monitored, restricted, and politicized. Surveillance did not operate only through people and files, but through architecture and geography.

In this context, espionage flourished. The proximity of opposing systems, separated by only meters, created ideal conditions for intelligence gathering, defections, and covert observation. The square’s location near key governmental buildings and former checkpoints placed it at the heart of Cold War tension.

Today, the presence of the Berlin Spy Museum at Leipziger Platz carries powerful symbolism. A site once defined by division and silence now hosts an institution dedicated to revealing what was hidden. Where movement was forbidden, visitors now circulate freely. Where information was controlled, history is openly examined.

By occupying this space, the museum does more than display espionage history. It reclaims a fractured geography. It transforms a former zone of fear into a place of memory, reflection, and critical understanding—reminding visitors that the Cold War was not only fought through ideology and weapons, but through cities, streets, and everyday lives.

The Berlin Spy Museum in the Capital of Espionage

After World War II, Berlin was divided into four sectors. They were controlled by the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union. This division transformed the city into a microcosm of global ideological conflict.

Consequently, West Berlin became a capitalist enclave surrounded by East Germany.

With the beginning of the Cold War in 1947, Berlin quickly earned a reputation. It became the capital of international espionage. Agents from across the world arrived, drawn by the constant flow of information across borders.

Meanwhile, refugees fleeing the East were interrogated at centers such as Berlin-Marienfelde. In some cases, they were even persuaded to return as spies. Thus, human intelligence became a primary source during the 1950s.

From Human Espionage to Technology

Over time, espionage methods grew increasingly sophisticated. Initially, intelligence relied almost entirely on people. Informants, couriers, and undercover agents risked their lives daily.

However, technological progress transformed these practices.

During the Cold War, American and British intelligence services carried out complex operations.

One of the most famous examples involved digging tunnels beneath East Berlin. The goal was to intercept Soviet telephone lines.

These actions show how Berlin became a large-scale espionage laboratory.

At the same time, global powers invested heavily in new technologies.

Double agents were combined with hidden microphones, miniature cameras, and advanced surveillance systems.

As a result, espionage no longer depended solely on direct contact. Instead, it relied on devices capable of recording and transmitting information invisibly.

The construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 intensified control even further. Crossing from one side to the other became nearly impossible.

Consequently, Western agencies adapted their strategies. They focused increasingly on technical intelligence. Direct exposure to agents was deliberately reduced.

As a result, border crossings turned into highly sensitive pressure points. For decades, they embodied the fragile balance between confrontation and restraint.

Among them, Checkpoint Charlie became the most iconic. Located at Friedrichstraße, it was the best-known crossing point between East and West Berlin.

More importantly, it stood as a visible symbol of the Cold War division. American and Soviet tanks once faced each other here, only meters apart, in moments when a single miscalculation could have triggered open conflict.

At the same time, Checkpoint Charlie was a stage for human drama. It witnessed daring escape attempts, carefully orchestrated spy exchanges, and silent negotiations conducted under constant surveillance. Every crossing involved strict controls, identity checks, and an atmosphere charged with suspicion. Even routine movements carried political weight.

Furthermore, the checkpoint exposed the psychological dimension of espionage. Fear, uncertainty, and anticipation shaped every interaction. The border was not only physical; it was mental and emotional.

The transition from human espionage to technology reveals more than a change in tools. It exposes a shift in how power, control, and information were understood during the Cold War. Berlin stood at the center of this transformation, where human risk gradually gave way to technical precision.

A Museum Also Designed for Children

At first glance, the Berlin Spy Museum may seem unsuitable for children. However, the opposite is true.

Young visitors are often fascinated by spies and mystery. Here, they learn that espionage existed long before the internet.

Through touchscreens, interactive maps, and games, children discover ancient encryption methods. They experiment with the Skytale, Morse code, and cipher disks.

One of the most surprising elements involves messenger pigeons equipped with mini cameras. These were considered early drones. Original Enigma machines also stand out.

Digital stations allow visitors to encrypt messages or test password security.

Interactive Exhibitions and Hands-On Experiences at the Berlin Spy Museum

One of the great attractions of the Berlin Spy Museum is, without a doubt, its interactive approach. From the very beginning, visitors stop being passive observers and become active participants in the experience. In this way, the visit invites people to touch, test, and experiment.

For instance, it is possible to decipher secret codes, analyze real surveillance images, or test one’s powers of observation in different simulated scenarios.

Through these activities, visitors gain a clear and accessible understanding of how intelligence services actually work. At the same time, they discover the skills required to move within the world of espionage.

Among the most iconic spaces is the famous laser maze. Here, theory turns into action. In this room, visitors must cross a space filled with beams of light without triggering the alarms.

To succeed, they need to jump, crouch, or even crawl across the floor, completing the mission in under two minutes.

For this reason, the maze has become one of the museum’s most popular attractions. This experience is especially appealing to families, school groups, and children’s celebrations.

At the same time, it maintains a strong educational component. Play, coordination, and concentration are combined within a controlled and safe environment.

In addition, the museum houses more than 300 original pieces of espionage equipment.

Throughout the exhibition, visitors encounter ingenious objects such as guns hidden inside lipstick tubes, microphones concealed in books, or devices camouflaged in high-heeled shoes.

Each item reveals the extent to which creativity and inventiveness became essential tools in contexts of conflict and constant surveillance.

Taken together, these hands-on exhibitions reinforce the idea that espionage is not only something to observe—it is something to experience.

Ultimately, it is this blend of knowledge, participation, and surprise that makes the Berlin Spy Museum such a memorable visit.

Memory, Human Rights, and Reflection

Beyond spectacle and technological curiosity, the Berlin Spy Museum proposes a necessary pause. It invites visitors to look with critical distance and to question the consequences of what they are seeing.

It does not limit itself to displaying intelligence techniques, devices, or strategies. Instead, it opens a space to consider how espionage has shaped societies, individual lives, and structures of power.

Throughout the exhibition, several sections address essential issues such as human rights, mass surveillance, the control of power, and the fragility of freedom. These themes do not appear as side notes. Rather, they function as transversal axes that run through the entire museum narrative.

Visitors come to understand that behind every surveillance technology there were political decisions, legal frameworks—sometimes nonexistent—and people directly affected by these systems of control.

In this space, something is always present: a sensation suspended between fear and hope. The atmosphere of the museum conveys the constant tension that marked entire generations. It is not only about historical information, but about an emotional experience that accompanies each room.

Within this context, espionage ceases to be perceived solely as a secret practice associated with cinema or geopolitics. Instead, it is revealed as a tool with profound social and political implications. On the one hand, it can be presented as a mechanism of protection and state security. On the other, it can lead to persecution, censorship, repression, and systematic control of the population.

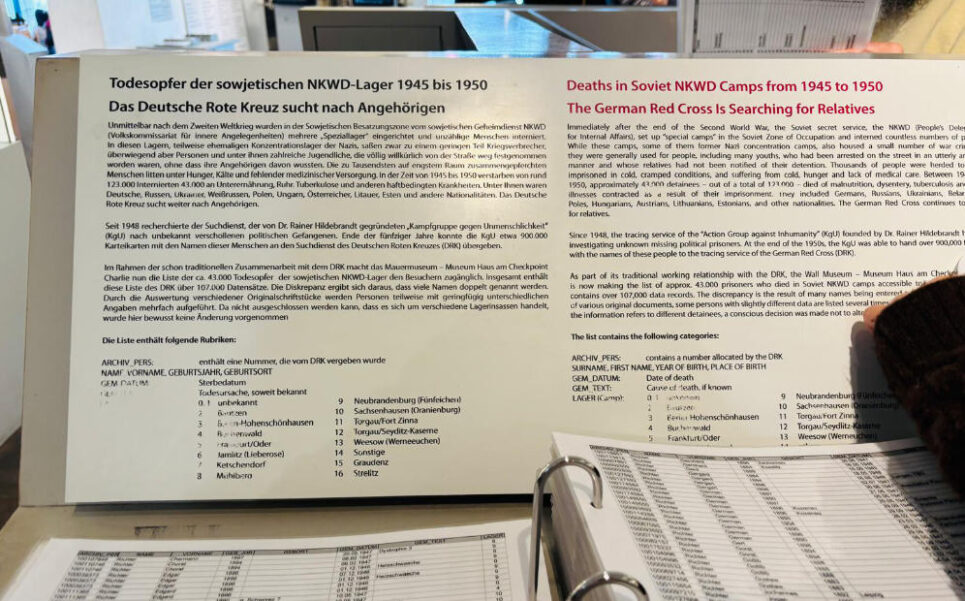

Some sections confront visitors directly with the human consequences of these systems. It is possible to see lists compiled by the Red Cross with the names of missing persons, documents that speak of prolonged absences, broken families, and uncertain fates. These records, seemingly cold, carry the weight of personal stories marked by silence and uncertainty.

Likewise, the museum displays objects that evoke desperate attempts to escape. Among them are real vehicles used to flee unlivable situations—contexts unbearable for the mind and the soul. These elements serve as reminders that, for many people, espionage and surveillance were not abstract concepts, but forces that shaped every daily decision.

The museum also establishes clear connections between these practices and broader historical struggles. References appear to figures such as Mahatma Gandhi, whose philosophy of nonviolent resistance offers a contrasting perspective on information, power, and ethics. These counterpoints expand the discussion and place espionage within a deeper reflection on the moral limits of control.

In this way, espionage is inserted into a larger debate on justice, human dignity, and historical responsibility.

It is not only about what was done, but why it was done, whom it benefited, and whom it harmed. Remembering these stories thus becomes an act of active memory.

Finally, the Berlin Spy Museum does not remain anchored in the past. It also raises uncomfortable questions about the present and the future.

In a hyperconnected world, where digital surveillance is part of everyday life, visitors leave with open questions: who is watching, for what purpose, and at what cost?

Thus, this section transforms the visit into something more than a museum experience. It becomes an invitation to reflect on power, memory, and freedom in our time—reminding us that fear and hope continue to coexist wherever history has not yet fully come to a close.

Conclusion: Why Visit the Berlin Spy Museum

The Berlin Spy Museum is an essential visit for anyone seeking to understand history’s hidden side. Through original artifacts, interactive technology, and strong educational intent, it offers much more than an exhibition.

Moreover, Berlin itself provides the perfect setting. Its divided past and Cold War legacy give the narrative real weight.

Ultimately, the Berlin Spy Museum honors those who worked in secrecy. It reveals how information, strategy, and silence shaped history. It is a place where mystery meets memory. A space that encourages curiosity and critical thinking. Because understanding espionage is, in the end, another way of understanding the world we live in.