Photography offers us a unique window into the soul of the world. In every image, there is meaning—something that shapes the way we see everything around us. Every day, photographs not only illustrate but also interpret reality. We live surrounded by images that decide what we remember and what we forget. In this sense, an image is not merely a reflection; it is a construction of meaning.

The power of the image does not lie solely in what it reveals, but also in what it suggests. Framing sets boundaries, depth of field creates hierarchy, and light shapes emotion. To understand its power is to understand how technique, perception, and intention intertwine to narrate the present.

Photography

Let us begin with the root of the word itself. Photography comes from the Greek phos, meaning “light,” and graphos, meaning “writing.” In its purest essence, to photograph is to write with light, to trace a single instant onto the surface of time. Every image, then, is born from the encounter between brightness and shadow, between the visible and the invisible.

From its origins, photography has existed as a dance between science and art. Its fundamental technical principle—the camera obscura—is almost a metaphor for vision itself. It is a sealed space where light enters through a small opening and projects, on the opposite wall, an inverted version of the world.

Of course, much has changed since then. Yet modern cameras have not abandoned that ancestral magic. They have simply refined it. They have added lenses to sharpen focus, mirrors to correct the image, and digital sensors to replace the old photosensitive plates. Still, the miracle remains unchanged: the light that touches reality becomes memory.

Before cameras existed as we know them today, the first attempts to capture an image were chemical and painstaking.

Heliography and the daguerreotype, developed in the 19th century, marked the first steps toward a visual revolution. Fragile and expensive as they were, these processes opened the door to new ways of seeing. With them, humanity realized it could stop time—that it could make the trace of existence visible.

The rise of photography coincided with the arrival of industrial modernity and the rise of positivist thinking.

At that moment, the camera became a tool for knowing, measuring, and recording. People sought objectivity, evidence, and documentation.

Yet photography quickly surpassed its scientific purpose. In more sensitive hands, light transformed into emotion, narrative, and poetry.

The inventors of the 19th century improved both technique and materials. Photography evolved from wet collodion to dry plates coated with silver bromide.

Then, in 1888, Kodak’s first roll film democratized the act of seeing.

Since then, every click of the shutter has been an echo of that early revelation: the discovery that light can tell a story.

This is how photography was born—from a blend of scientific curiosity and human wonder. And although today’s cameras are digital and the darkrooms live in the cloud, the gesture remains the same. To photograph is an act of faith. It is the belief that for just an instant, light can stop time itself.

Technique as Language

Technique is not just a tool — it is a way of speaking. Every photographer writes with light, but also with intention. Framing defines, light interprets, and exposure translates emotions. What may seem like a simple technical choice — opening the aperture, moving the lens, adjusting the ISO — becomes a declaration of meaning.

From the first daguerreotypes (which differ from other early photographic devices because the image forms on a mirror-like polished silver surface) to digital photography, technique has served as the bridge between reality and the human gaze.

But taking a photograph is not merely about mastering a device. It is about understanding that every technical decision shapes what the image says, how it says it, and, above all, what it chooses to leave unsaid.

A strong photograph is not built on talent alone; it rests on an awareness of form. In it, technique becomes language — and language becomes truth.

Every photograph begins with a choice: what to show and what to leave out.

Framing is never innocent. Light is never neutral. Technique is not an ornament, but the skeleton of the message. Everything has a reason to be. Every image contains an invisible architecture made of decisions. In that silent order of lights and shadows, the photographer shapes the world.

Composition and light have the power of the image to transform the everyday into a symbol. A strong shadow can suggest danger or melancholy; high exposure can evoke purity or hope. Technique, far from being an artifice, is the vocabulary through which emotion speaks. It doesn’t beautify — it communicates.

Artistic photography, for example, is born from deep intention. It does not aim to document or sell, but to feel and to make others feel. Each image is an intimate response from the photographer to the world: an emotion translated into light, an idea turned into form.

That is why it is called artistic photography. Art emerges from the desire to express the invisible, to give meaning to what the everyday gaze cannot grasp. In artistic photography, nothing is accidental. Each frame, each shadow, each visual silence is guided by a poetic will: to transform reality into experience.

This intentionality is what sets artistic photography apart from other branches. Documentary photography seeks to represent the world objectively. Commercial photography is designed to highlight a product or service. Artistic photography, however, has the freedom to reinterpret. It does not reproduce — it recreates. It does not inform — it evokes. And within that fundamental difference lies its most human power.

Meanwhile, in the realm of photojournalism, communication acquires an ethical dimension.

In photojournalism, ethics is not optional — it is the backbone. Credibility and integrity depend on it. Being faithful to reality, respecting victims, and avoiding any form of manipulation are not mere guidelines; they are commitments to the truth. Ethical responsibility protects not only those who appear in front of the lens but also the value of the visual narrative itself.

High contrast can convey tension or urgency, while soft light can humanize even conflict. In this space, the photographer faces a constant dilemma: how to translate the rawness of reality without stripping it of its humanity.

Photojournalism is a complex and captivating field. Its purpose is not only to capture images but to tell visual stories in real time. It unfolds across print, digital, and audiovisual media, encompassing multiple genres, including news photography, reportage, journalistic portraiture, and the photo essay.

Unlike artistic or studio photography, photojournalism is anchored in the present. It seeks to bear witness, to become the visual memory of what might soon be forgotten. From war to sports, from politics to daily life, every frame contains a narrative about a world in motion.

Yet in the digital age, editing heightens responsibility. A single click can alter tones, erase imperfections, or shift context. Visual ethics has become as crucial as technical skill. Every adjustment — however subtle — becomes a narrative decision.

When used properly, editing can enhance quality, impact, and expressiveness. Adjusting contrast, exposure, or color can enhance a message without compromising its integrity.

However, the risk of manipulation is always present. In a world where images travel faster than words, technique must uphold truth — not replace it.

A camera, in careful hands, is a tool of truth. In careless hands, it can distort the very world it seeks to reveal. This is why a photographer does not merely master technique — they honor it. Because in every click beats a moral decision, a gaze that shapes what the world will remember tomorrow.

A New Gaze: Artificial Intelligence and Creation

Every technological advance has redefined the way we look at the world. From the first camera obscura to the digital era, photography has evolved without losing its essence: capturing light to give shape to memory. This essence is part of the power of the image, a power that has guided photographers since the beginning.

Today, however, a new revolution is redefining that gaze. Artificial intelligence not only assists the photographer but also creates on its own. We are in an unprecedented territory where the human eye shares space with the machine’s eye, and where the line between what is created and what is generated becomes blurry. This challenges the power of the image in ways we could not have imagined before.

Photography, at its core, is the art and technique of capturing light to create a lasting image. It is the union between the physical and the emotional: the science that stops an instant and the art that gives it meaning.

Since its invention, it has been a mirror of time and a tool of collective memory.

However, the arrival of artificial intelligence has profoundly transformed this art. The boundaries between the real and the imagined fade: algorithms can generate non-existent faces, impossible landscapes, or scenes that resemble memories. This raises essential questions about the power of the image when it is no longer tied to reality.

This raises a fundamental question: What happens to the power of the image when the image no longer needs reality? Is it still photography?

AI can amplify creativity and open visual paths once unimaginable, but it can also erode trust. If everything can be manufactured, what place does truth hold?

Here emerges the new responsibility of the photographer: to preserve authenticity in an ocean of simulacra. In this digital landscape, technique remains vital, but ethics and intention become the most precise compass.

Amid this digital transformation, where artificial intelligence redefines the limits of creation, documentary photography stands as a reminder of what is essential: human connection. Faced with algorithms that fabricate impossible worlds, the lens of the documentarian returns to the tangible, to what has been lived. It reminds us that the most valuable light is not the one generated by a machine, but the one born from encounters with reality and with those who inhabit it — a reminder of the power of the image in its purest form.

Documentary Photography and Photojournalism

Documentary photography and photojournalism share a common root: the power of the image to reveal what often goes unnoticed.

Both genres are born from the need to look deeply, to capture not only what happens, but what it means. In times when artificial intelligence can invent non-existent worlds, these visual languages recover something essential: the truth of what has been lived.

Beyond artifice, the camera becomes a sensitive witness, an extension of human consciousness that observes, feels, and translates the world into light and shadow.

Documentary photography does not seek to invent, but to reveal. It is an act of presence, of empathy, and of patience. Each image is the result of a gaze that pauses, that observes without haste, that attempts to understand.

From the first reporters of the 19th century, interested in documenting the political and social changes of their time, to contemporary authors who document humanitarian crises or the impact of climate change, the purpose has been the same: to understand the world through its wounds and its hopes.

Documentary photography possesses a unique strength: that of translating reality into visual emotion. In it, words become unnecessary because the image speaks its own language.

Sebastião Salgado, one of the great masters of the genre, has turned his camera into an instrument of denunciation and compassion. In his photographs, pain and beauty coexist; the gaze becomes an ethical, almost spiritual act. His work reminds us that the power of the image can move and transform the conscience of the viewer.

Throughout history, documentary photography has developed certain essential traits that define it:

** Objectivity: it seeks to capture reality without significant manipulation.

** Authenticity: it reflects life and society as they are, without embellishments or idealizations.

** Preservation: it documents moments and events for their conservation and study in the future.

** Visual narrative: it uses images to tell stories and convey messages with emotional depth.

** Personal style: each photographer imprints their sensitivity and their way of observing the world.

Thus, the documentarian not only records, but they also interpret. Their gaze becomes a bridge between what happens and what we feel.

If documentary photography is nourished by contemplation, photojournalism is defined by immediacy. It is the art of stopping time at the precise moment when history happens. Every shot requires instinct, speed, and courage, but also sensitivity and ethics.

The photojournalist does not seek beauty, but the truth of the moment; however, within that urgency, a form of unexpected poetry can arise.

The characteristics of photojournalism reflect its living and committed nature:

** Timeliness: it focuses on events and situations of public interest occurring in the present.

** Visual impact: it pursues images that generate a strong impression and convey the emotion of the instant.

** Speed and opportunity: it requires being in the right place at the right moment.

** Ethics and responsibility: respect for human dignity and the truth of events is its moral foundation.

To photograph is to put the head, the eye, and the heart on the same axis.” – Henri Cartier-Bresson –

Information and awareness: it seeks to inform and, at the same time, awaken reflection and empathy.

Photography is technique, intuition, and humanity interwoven in a single gesture. Through the lens, the photojournalist becomes a narrator of the present, capable of stopping chaos and giving it meaning.

In both disciplines — documentary and journalistic — the power of the image lies in its ability to transcend time and awaken awareness.

It is not only about recording what happens, but about honoring the truth of what is lived. In an era in which images can be created without ever having existed, the human photographer must remember their oldest purpose: to witness without manipulating, to move without lying, to create without betraying reality.

Perhaps, rather than a threat, artificial intelligence is a mirror that invites us to redefine what it means to create. The difference does not lie in the tool, but in the intention that guides the gaze. The future of photography does not depend on technology, but on those who hold the camera with consciousness and respect. Because, in the end, the power of the image does not reside in the machine that produces it, but in the soul that illuminates it.

Gazes That Opened the Way

Throughout history, photography has been much more than a technical tool: it has been a way of thinking, of feeling, and of transforming reality.

The power of the image lies in its ability to open questions, to move, and to make visible what so often goes unnoticed.

Behind every great photograph, there is a gaze that changed the way we understand the world. Each shot is an invitation to see differently, to observe carefully that which reveals as much about the other as about ourselves.

The history of photography is woven with names that opened aesthetic and ethical paths, with gazes capable of altering our perception of the world. Each of these artists understood that the power of the image lies not only in what it shows but in what it provokes: discomfort, empathy, reflection, or wonder.

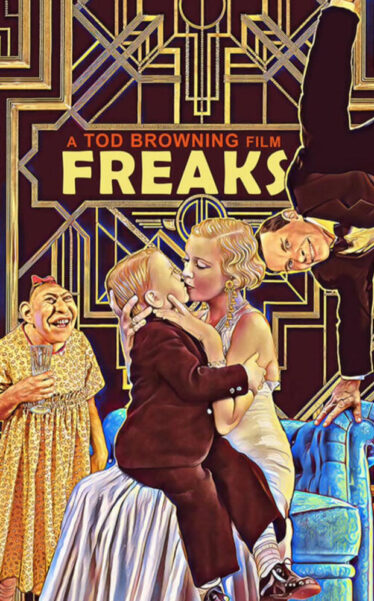

Diane Arbus portrayed humanity in the margins. An American photographer known as the photographer of freaks, Arbus transformed the strange into a mirror. Inspired by Tod Browning’s film Freaks, she decided to focus her lens on those who lived outside the norm: twins, transvestites, mentally ill individuals, circus performers, or dysfunctional families.

Her pioneering use of fill flash (daylight flash) accentuated the features of her subjects with an almost theatrical rawness. In her photographs, “normal” people could appear disturbingly abnormal. Arbus did not seek pleasing beauty, but uncomfortable truth. Her portraits confront the viewer with their own judgment, turning photography into a space of moral and aesthetic confrontation.

Sebastião Salgado, Brazilian photographer, found poetry in the harshness of human labor. His camera became a tool of denunciation and compassion. Linked to the socio-documentary tradition, Salgado has dedicated his work to showing the living and working conditions in impoverished regions, conflict zones, or displaced communities. Series such as Workers or Genesis reveal his ethical and visual commitment: in them, suffering and dignity coexist in a balance of light and shadow that dignifies the human being. In his work, the power of the image is also a power of transformation: the power to sensitize and mobilize consciences.

Vivian Maier turned the street into an intimate mirror. An American photographer and nanny by profession, she developed a colossal body of work that remained hidden for decades. Her gaze rested on the everyday: reflections in shop windows, children playing, lonely elderly people, fleeting gestures.

Without the means to develop many of her rolls, Maier photographed out of pure inner necessity, without seeking fame or recognition. Her street photography, marked by curiosity and empathy, demonstrates that the power of the image can also reside in anonymity: in observing without being seen, in capturing the poetry of the ephemeral.

Ansel Adams made nature speak with its own powerful and silent voice. An American photographer and pioneer of modern landscape photography, he developed, together with Fred Archer, the Zone System — a technique that allowed precise control of exposure and contrast to reproduce the full tonal range between absolute black and pure white.

His technical mastery combined with a profound reverence for nature. In his work, light becomes language and the mountain becomes a spiritual symbol. Adams understood that the power of the image could also serve to preserve the world: his work was key in the creation of national parks and in environmental advocacy.

Today, artists such as Zanele Muholi, Cristina de Middel, or Gregory Halpern continue expanding the boundaries of the gaze. Muholi celebrates the identity and resistance of the South African LGBTQ+ community; De Middel combines reality and fiction in projects that question the truthfulness of documentary photography; Halpern, with his dreamlike aesthetic, explores the imperfect beauty of the American landscape.

All of them understand that the camera not only records but interprets; that the power of the image lies in its ability to connect worlds, to humanize distance, and to make the invisible visible.

In the end, each generation inherits the challenge of reinventing the gaze. In times of visual saturation, the power of the image reaffirms itself not through spectacle, but through authenticity and its ability to be reborn in every eye that contemplates it. Photography remains a living language: it changes, it challenges, and it transforms us with every new frame.

The difference in gazes: women and men behind the lens

Every image is born from a gaze. And every gaze, from a story.

Over time, photography has been a witness to humanity, but also a reflection of the person holding the camera. There is no neutrality in the act of seeing: the power of the image is tied to the power to look and to be seen.

For decades, the lens was dominated by masculine voices that narrated the world from their own center, while other gazes —silenced, made invisible, pushed aside— waited for their turn to speak.

Today, that multiplicity is emerging with force: women, dissident identities, and new sensibilities are redefining the photographic act as a space of dialogue, emotion, and resistance.

Although photography presents itself as a universal language, not all voices have had the same echo within it. Throughout much of its history, the male gaze dominated the visual narrative of the world, imposing aesthetic, thematic, and symbolic canons. However, over time, the power of the image opened space for new perspectives —female, dissident, marginal— that transformed the visual language from within.

The photographers, armed with sensitivity, intuition, and rebellion, not only expanded the limits of the photographic arts but also demonstrated that to look is a political and profoundly human act.

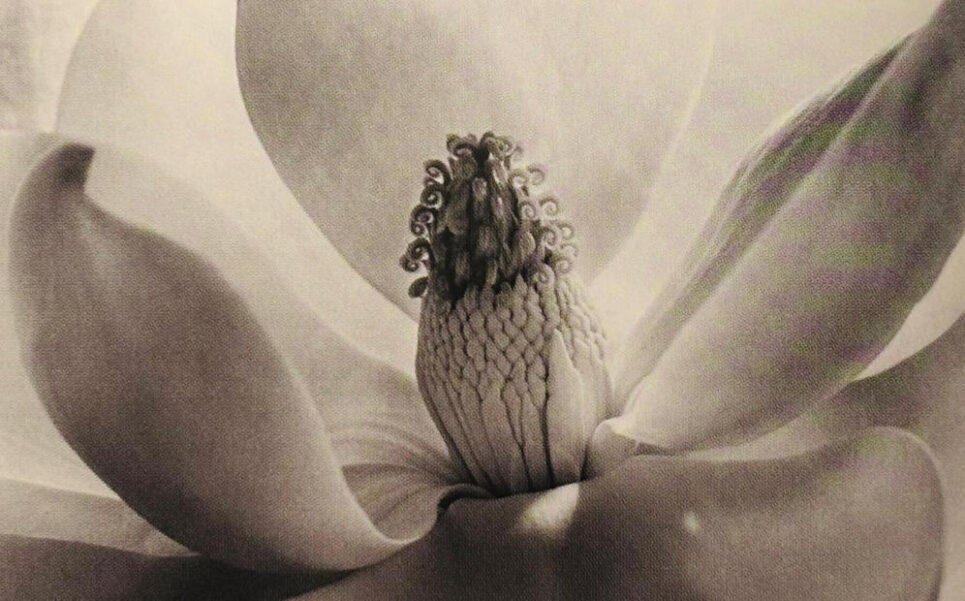

Imogen Cunningham (1883–1976) was one of the first photographers to integrate art and science within her work. A pioneer of portraiture, botany, and the female nude, she explored the sensuality of the everyday with sober elegance.

Her precise use of natural light and her attention to organic forms challenged the conventions of her time. Cunningham was part of Group f/64 alongside Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, advocating for pure photography, free of artifice, where sharpness and composition became visual poetry. In her work, the power of the image resides in subtlety: in the ability to find beauty in what seems insignificant.

Graciela Iturbide (b. 1942), heir to Mexican tradition and disciple of Manuel Álvarez Bravo, has dedicated her life to capturing the spirituality and rituals of deep Mexico. Her black-and-white photographs are bridges between the mystical and the everyday, between the sacred and the human. In series such as Juchitán de las mujeres or Los que viven en la arena, Iturbide turns the local into the universal. Each image is a silent ceremony that honors identity, death, the body, and memory. In her gaze, the power of the image is the power to preserve cultures, resistances, and ancestral silences.

Nan Goldin (b. 1953) brought the camera into the terrain of the rawest intimacy. Her series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is a visual diary documenting her life, her loves, her friends, and her LGBTQ+ community in 1980s New York. With a direct aesthetic saturated with color and emotion, Goldin transformed vulnerability into resistance and the exposure of the personal into a political act. Her photography is confession and testimony; art and survival. In her work, the power of the image manifests as living memory, capable of denouncing, healing, and moving.

Through their lenses, the private becomes public, and the vulnerable becomes strong.

While some photographers have sought immediate impact, many women photographers have leaned toward emotional resonance: the whisper behind the shout, the story hidden in gestures. Their images not only document but reinterpret the feminine, the human, the real.

This diversity of gazes strengthens the power of the image, reminding us that visual truth is not singular, but multiple. Each lens contributes a new emotion, a different interpretation of the world. Photography, when multiplied into many voices, becomes a space of dialogue and encounter.

In this exchange between men and women, between past and present, the power of the image reasserts itself as a language of transformation.

Plurality does not weaken photography; it enriches it. Within it converge all gazes —those observing from the margins and those looking from the center— to build a broader, more just, and deeply human vision of the world we inhabit.

Photography no longer belongs to a single gaze but to a chorus of perspectives that intertwine and contradict each other. In this dialogue between the intimate and the political, between the technical and the emotional, the power of the image is revealed: its infinite capacity for transformation.

Women photographers, with their intuition and courage, not only opened new visual territory but also reminded the world that seeing is also feeling.

And in that shared truth —between the one who photographs and the one who contemplates— photography remains alive: a light that changes hands but never stops illuminating.

Conclusion: the image that looks back at us

Every photograph is an open question. We do not only look at images: they also look at us, question us, confront us with who we are and what we fear to see. The power of the image lies in its ability to make us feel, think, and remember.

We live in an age saturated with images, but only a few manage to transcend. The ones that move us, that invite silence, or force us to stop, are the ones that leave a mark. Not because they are perfect, but because they are alive. Because behind the lens there was an honest gaze, a human intention.

Photography remains a territory where technique meets emotion and where light becomes language. Every photographer, every woman photographer, seeks in the radiance of the world some form of truth, a crack through which to look at the human condition. Sometimes that truth hurts; other times it comforts. But it always illuminates.

And as long as people are willing to search for meaning in the act of looking, the power of the image will continue to be one of the most deeply human gestures. Within every photograph hides a story that not only captures the moment but also transcends it. Thus, the image looks back at us, reminding us that seeing is not merely observing: it is recognizing ourselves, again and again, in the shifting mirror of light.