Mipanocha Rurru is a Mexican artist; she is from the sacred forest area south of the Ajusco Mexico City; a city known for creating an imaginary and rearranging all sorts of visual and ideological values that have been continuously separated by the forces of moral repression and historical oblivion.

Her work

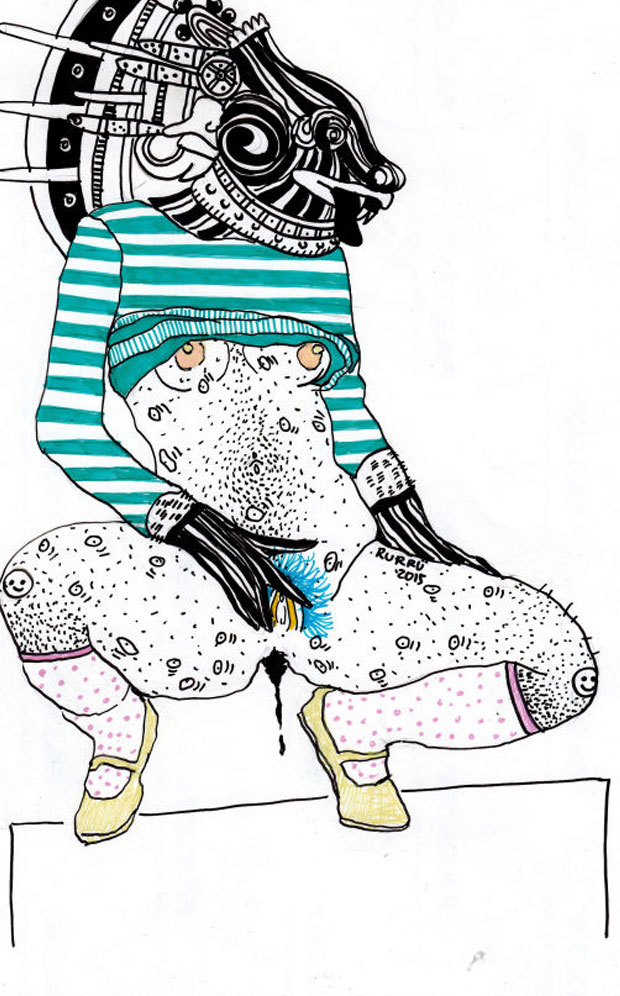

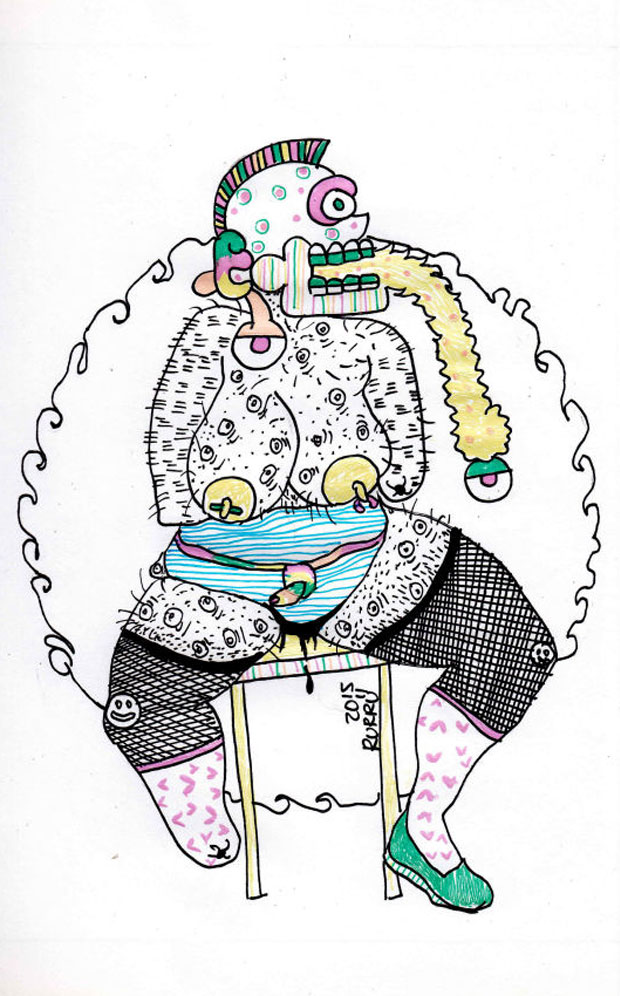

In her work she brings together a young and sensual pre – Hispanic iconography with the symbolism of queerness in the XXI century, Mesoamerica.

At that moment, fire casted light upon natural painting on the bodies. Now the neon ink runs without end, a fire that is not appeased. It is simple: the Eros is as linked to humanity as fear itself.

Her work is a critical reflection that opposes the exclusion or marginalization of bodies, thereby, to root a landslide of all identity fictions. It is impossible to constrain her body of work in a specific plastic technique.

The perfect examples are the many tutorials Rurru has on YouTube. She has exhibited her work in Berlin, Bremen, Mexico City, Bordeux, Lisbon, Barcelona, Chicago, Buenos Aires and Bogotá.

Challenges for art

B: What is an ongoing challenge for art?

M.R.: That attempt or communicate something and so becoming political so that it goes beyond the aesthetic. There are many tools in contemporary art, as example, the fanzine is an “easy” and simple means used to reach many people and containing both text and illustrations.

Texts and illustrations that have been artistically created but have a function that surpasses the sensible side, it helps in observing different artistic communities.

B: What are your areas of interest? What discipline and technique are the most practical?

M.R.: Drawing and video, and also do some animation. My subjects are magic, Mesoamerican civilizations, ritual, myths, and legends.I identify with the queer wave its cargo of sexual dissidence.

Let us say that there were two paths used achieve a bodily release without making it trivial.

I am interested in the heinous. I am also in favor of respect towards the rights of indigenous groups and the preservation of their cultures and territories.

How come the vast majority of the society admires indigenous people, the ones that are already dead, but at the same time mistreat the current indigenous folk?

B: Why do you recapture pre-Hispanic iconography?

M.R.: Mainly because I like its aesthetics and symbolism. I try to make a personal reinterpretation of some legends and rituals of a sexual nature that some people from the Mesoamerica had.

In this sense, I focus my attention on the Huasteca and Maya cultures: the first was explicitly erotic in everyday life, while the second had a ritual mysticism to experience that eroticism.

Meaning that, the Mayas attributed sex to a sacred charge and huastecos to nature. As a matter of fact, any object can be sacred, this given that it reveals something other than itself. Consequently the body becomes sacred when it stops being a simple profane object and when showcasing a manifestation of hidden forces.

B: It may seem shocking to us but probably for this ancient cultures it was a means of neutralizing sex in the everyday

M.R.: I think that it’s just what Mircea Eliade is saying: mystical experiences are influenced by a historical moment. By this I mean that they are represented in very specific situations and although some have a local destiny (that other cultures cannot reach) other have or obtain universal values.

B: What is your perspective towards the human body, nudity and gender roles?

M.R.: Nudity should be seen for what it is, like a natural, normal, random thing. The same goes for the human body. In regards to gender roles, I think it is amusing how the personal reconstruction takes place and changes time and again, molding it to our needs, to our likes and dislikes.

B: Why do you use neons? What aesthethic association do you have with it?

M.R.: Before I did use a lot of pastel colors because I like it visually, but I’m experiencing more with neon because I like the effect it provides when you give some light: it looks a bit mystical, magical, like a fairy tale for small children. I use the turquoise color a lot because it was widely used in the Mesoamerican civilizations.

The ritual to the goddess Tozi or Tlazoltéotl consisted of skinning a girl at the hands of a high priest, who later danced with her skin, and so Tlazoltéotl represented the goddess. It was a dance that took place around others with a stone phalluses simulating or having an actual priest embodiment and then having intercourse with the goddess. It was a fertility ritual.

B: What path has your work followed?

M.R.: I started doing drawings that slightly tilted towards sexual explicitness, then I got more into legends and sexual rites in Mesoamerica, and the various depiction of the bodies. Now I’m more into fluids, into the menstruation.

B: What about menstruation?

M.R.: With the meaning and interpretation of menstruation in Mesoamerican society. Mainly because they were afraid of it, menstruating women were not allowed to participate in rituals; men couldn’t have sex with them or even look at them during those days. It was believed that if a child looked at a woman with her period, he or she would die. They were completely isolated.

The main substance for life

But, it was also considered a sacred and magical liquid that in many legends is the main substance for life. For example, the Nahuatl believed that women got their periods because Camazot (the bat god or sacred bat) bit a chunk Xochiquétzal’s vulva (the goddess of flowers) and that piece of vulva was taken to Mictlan (the underworld) where Mictlantecuhtli (god of the underworld and the dead) planted it and from it fragrant flowers were born.

Another example is that the Maya believed that Ixchel (goddess of love) became pregnant because a Balam (jaguar witch) is hidden in a tree and pours a drop of semen on the head of Ixchel. Afterwards she becomes pregnant but her father does not think so she tells him and sends him to dismember her with the help of 4 owls.

When they are about to kill her, the owls feel pity for her. So, Ixchel puts her menstruation in a pumpkin, the owls take it to her father and tell him that those are the last blood drops of her heart, her father stays at ease.

The art, the body and the sacred were fundamental aspects of Mesoamerican life after the conquest, colonial and modern period have been succeeded in their practices by the prejudices of a prohibitive and repressive society.

Our Roman Catholic heritage has suggested for a long period to entire generations, that evil is emanated from their bodies and sex, when in fact they are only source of life and pleasure.

It is an achievement of contemporary culture, sexual liberation not only of women but of society in general, and, within that society Mipanocha Ruru’s proposals arise. They are infinitely necessary and attractive in order to give a renewed meaning to our sex practices and our view of a beautiful body.