The act of naming and being named, has been since immemorial times, an act of magic, of power. The great complexity of the language that we study rigorously through its grammatical and syntactical compositions, contains a deep mystery that neither the finest pun has managed to uncover.

A strange intuition tells me that there is something more, something that my human capacity will never manage to understand. And that is the reason why these are mysteries, although through centuries of life on earth humans have managed to invent ingenious technologies (including language) to explain the unexplainable.

To name it, to grasp it, to transmit it, and remember it: are all glimpses of a desire to know the origin of death, the as above, so below.

The human capacity

This human capacity is what has given us power over other species, it is the way of enchanting, of forging through speech, of naming ourselves and everything around us.

Isn’t this, perhaps, the way Spaniards seized territories that were new and unknown to them? The word, like magic, is dangerous when it is malicious. And so it was that the Iberian peninsula, replaced with a language many others and seized lands, wealth and souls since “colonization is primarily an act of renaming.”

It is through such action that today those people that were spell bounded by the power of written words, and reuniting with their traditional and denied knowledge and are returning back to singing, languages, ceremonies, magic, are turning back to themselves.

Being able to find an indigenous community that is alien to the Western influence, or that has been slightly marked by it, to the point of maintaining their tradition unbroken, is almost as unusual as the recognition (inside of what is known as indigenous literature) of the development of a new method that works for an emancipation that takes place on the edge of the post colonialist current.

Which, on the other hand, is not configured as a new literary genre, in the first instance because that “making part of” a small circle is far from the purposes that indigenous intellectuals or writers actually have.

Writing

For them the approach to the act of writing was at first a cultural imposition, that was then converted into (chumbe) coloured weaving which tells the story about themselves and their people.

This ingenious appropriation of a foolproof mechanism as writing is, by those who have been its victims, is a gimmick defense that the traditional dichotomy between orality and literacy dissolves to accommodate the system of complementary opposites: one can not exist without the other, there is no day without night, no life without death, what is above is not possible without what’s below.

This idea comes from the indigenous thought, that instead of separating more the polar opposites, makes them attract to each other, or in the best case, blends them with the Andean pachakuti style, announcing a time when the above will be below and the below on top.

Pachakuti literally means an earthquake, earth movement, “as to the symbolic, is more accurate to speak of cosmic investment […] pacha is an expression of the cosmos as a womb, as the uterus, as pluriversal order. Pacha is the space-time continuity.” (Rocha, 109, 2012).

Mallki Wiñay’s poems, a devoted poet from the Yanacona community, are as described by its name in Quechua, a “root remaining in time.” They are a physical test of the eternal return, the time-space spiral reflecting pachakuti.

In his poems “the stream we share is such as the poetry that inspires the permanent flowing of a river: returning through other paths onto the value, the plurality, to the freshness and beauty of the meaning of words” (Rocha, 75.2012).

The approach I am trying to do, steps away from having an indigenous character, for it not only concerns the renascent community from which these poetic songs come from. Even though it is designed by and for indigenous groups, the reception inside the Yanakuna-mitmakuna is largely indifferent to the aesthetic values and the manifestation of the spirits of water, the earth, fire and air throughout language.

For them, communication with these elementary fundaments has become part of their reality since the beginning of time, and a poem does not make a difference in such a relationship, as it is for us, who have forgotten, generations ago, the meaning of a simple life. The reading of these poetics brings us a remembrance of it.

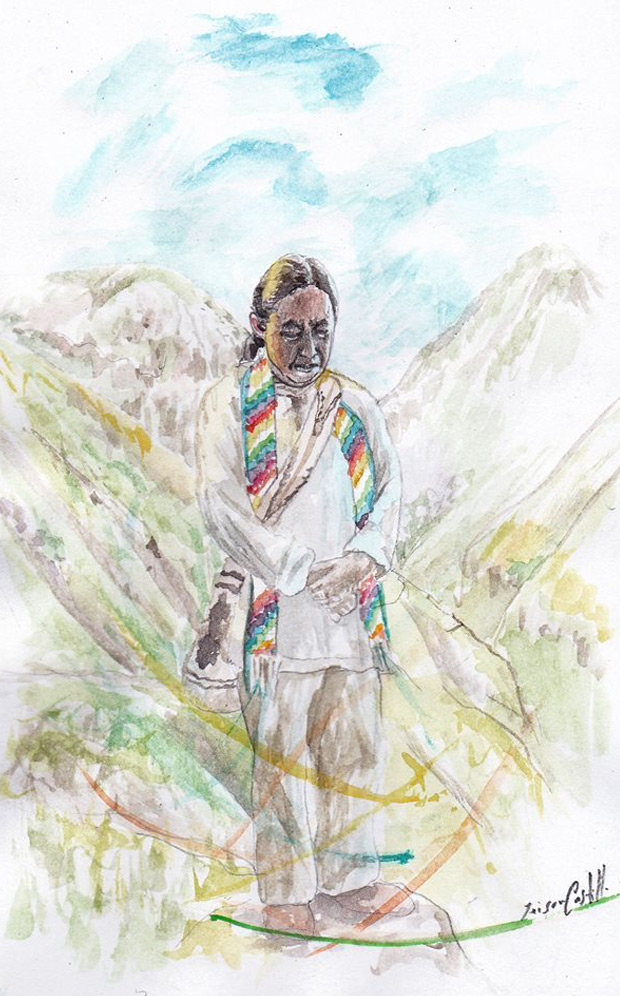

From the above, Fredy Chicangana, -name tax- is acutely aware and therefore his work as a “poetic root” into the Yanakuna-mitmakuna community is of unquestionable importance, concerning the process of cultural recovery their experiencing, and of a long history of silence and oblivion, high in the mountains and moors of the Colombian Massif, making their historical reality in a renascent state.

They are actually “giving birth” to new ideas, new ways of reassuming their songs, their language and tradition, in a territory that for the older knowers, the body represents the womb of Pachamama, Mother Earth. And the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta is the heart of the world. Not surprisingly the oraliterary pachakuti meets its cosmic role in this part of the world that signifies pacha, belly, womb.

Although the Yanakuna-mitmakuna cannot recover the territory that was taken from them, they will continue to strengthen the weakened roots that have managed to survive over time. It does not much matter if they cannot climb to the lagoon where the “gold snake drank water” which is no longer there, or if on the Jukas’ territory, he is no longer wandering to protect animals in the forests and moors which are diminishing too.

What matters is that they can rename (in Quechua) these beings and those places that make up their existence since immemorial times. The important thing is that they can call them within songs and ceremonies so that they do not disappear completely. Evoke them to keep the water flowing, for the sacred coca plant to regain its power of vision and strength, and no longer poison or illicit cultivation.

It is not resignation

It is not resignation, it is once again reaffirming their physical and spiritual existence, as they did on March 21, 1992 in the Guachicono pronouncement, given the sad fact that they still “did not appear in books or maps.”

How Miguel Rocha points out in the introduction to the literature collection of the southern Andes in Colombia, “the weakening of indigenous oral tradition can also be explained by a long drought in the mouth of past generations who have abstained or forgotten the words of origin “(Rocha, 2010.159).

But this drought is more of an alarming problem when we see that rivers, lakes, ponds and caudal waters that belong to the belly of the world, also are drying. It is coincidence or does the intrinsic relationship between culture and territory is acting out its injury?

Attention is called up on the poetic water figure, which is the most recurrent and from which a mythical reconstruction of his legacy is done, as the son of water. Reminding the reader, both the Indian and the uprooted forgetful Western man, that beyond metaphors or myths, all sources arise from water.

An immanent truth

This is an immanent truth such as death is, it is inevitable: from water we come and to water we will return.

While there is water there will be life on Earth, which reminds us that we must appraise it and find solutions for the protection of this water in times of anger, not only symbolically but, more importantly, in a practical and experiential way.

The orality work of Fredy Chicangana is an updating of the long history of cultural resistance that characterizes indigenous peoples in the Cauca department.

With a much deeper purpose and in line with its mission to root spatio-temporal within the pacha, ie cosmic existence, within a weaving that unites cultures and thoughts.

This resistance is not satisfied only within the physical-material, political and social level, but rather to make the journey for universal cosmic memory that binds us all equally, with poetry becoming the thread that binds the fabric.