Since its creation, the United Nations has had many goals, one of which has been to achieve global nuclear disarmament. It was the subject of the General Assembly’s first resolution in 1946, which established the Atomic Energy Commission (dissolved in 1952). The Atomic Energy Commission was meant to make specific proposals for the control of nuclear energy and the elimination of atomic weapons and all other major weapons adaptable to mass destruction.

The United Nations has been at the forefront of many major diplomatic efforts to advance nuclear disarmament since.

In 1959, the General Assembly endorsed the objective of general and complete disarmament. In 1978, the first Special Session of the General Assembly Devoted to Disarmament further recognized that nuclear disarmament should be the priority objective in the field of disarmament. Every United Nations Secretary-General has actively promoted this goal.

Nuclear History

The first nuclear test was conducted in the New Mexico desert in 1945. It was called “Trinity” and it marked the beginning of the atomic age.

On August 6, 1945, towards the end of World War II, “Little Boy” was detonated over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Exploding with a yield equivalent to 12,500 tonnes of TNT, the blast and thermal wave of the bomb destroyed nearly 50,000 buildings and killed 70,000–80,000 people outright, with total deaths being around 90,000–146,000.

Little Boy was the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay. It was developed by Lieutenant Commander Francis Birch’s group at the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II, a reworking of their abandoned Thin Man nuclear bomb.

Only three days later, on August 9, 1945, “Fat Man” exploded over Nagasaki. It destroyed 60% of the city and killed 35,000–40,000 people outright, though up to 40,000 additional deaths may have occurred over some time after that. Subsequently, the world’s nuclear weapons stockpiles grew.

Fat Man was built by scientists and engineers at Los Alamos Laboratory using plutonium from the Hanford Site.

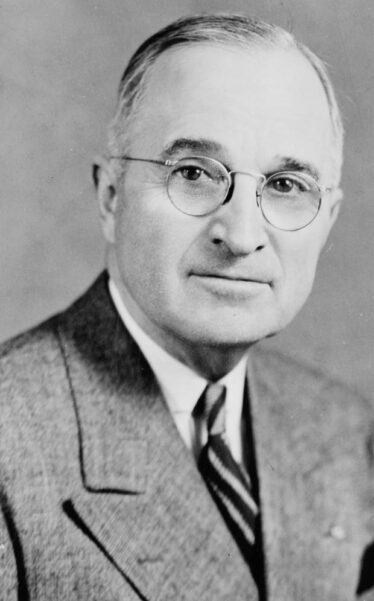

In 1946 the Truman administration commissioned the Acheson-Lilienthal Report, which proposed the international control of the nuclear fuel cycle, revealing atomic energy technology to the USSR, and the decommissioning of all existing nuclear weapons through the new United Nations (UN) system, via the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC).

With key modifications, the report became US policy in the form of the Baruch Plan, which was presented to the UNAEC during its first meeting in June 1946.

As Cold War tensions emerged, it became clear that Joseph Stalin wanted to develop his atomic bomb and that the United States of America insisted on an enforcement regime that would have overridden the UN Security Council veto. This soon led to a deadlock in the UNAEC.

Operation Crossroads was a series of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean in the summer of 1946. Its purpose was to test the effect of nuclear weapons on naval ships. Pressure to cancel Operation Crossroads came from scientists and diplomats.

Manhattan Project (was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the U.S.A. with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada.) Scientists argued that further nuclear testing was unnecessary and environmentally dangerous.

Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when a hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific contaminated the crew of the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon.

What is nuclear disarmament?

The first thing we need to do is try and understand what nuclear disarmament entails. Nuclear disarmament is the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons. Its end state can also be a nuclear-weapons-free world, in which nuclear weapons are eliminated. The term denuclearization is also used to describe the process leading to complete nuclear disarmament.

Another thing that is important to note is that disarmament and non-proliferation treaties have been agreed upon because of the extreme danger intrinsic to nuclear war and the possession of nuclear weapons.

Peace movements emerged in Japan and 1954 they converged to form a unified “Japanese Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs”. Japanese opposition to the Pacific nuclear weapons tests was widespread, and “an estimated 35 million signatures were collected on petitions calling for bans on nuclear weapons”.

In the United Kingdom, the first Aldermaston March organized by the Direct Action Committee and supported by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament took place on Easter 1958, when several thousand people marched for four days from Trafalgar Square, London, to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment close to Aldermaston in Berkshire, England.

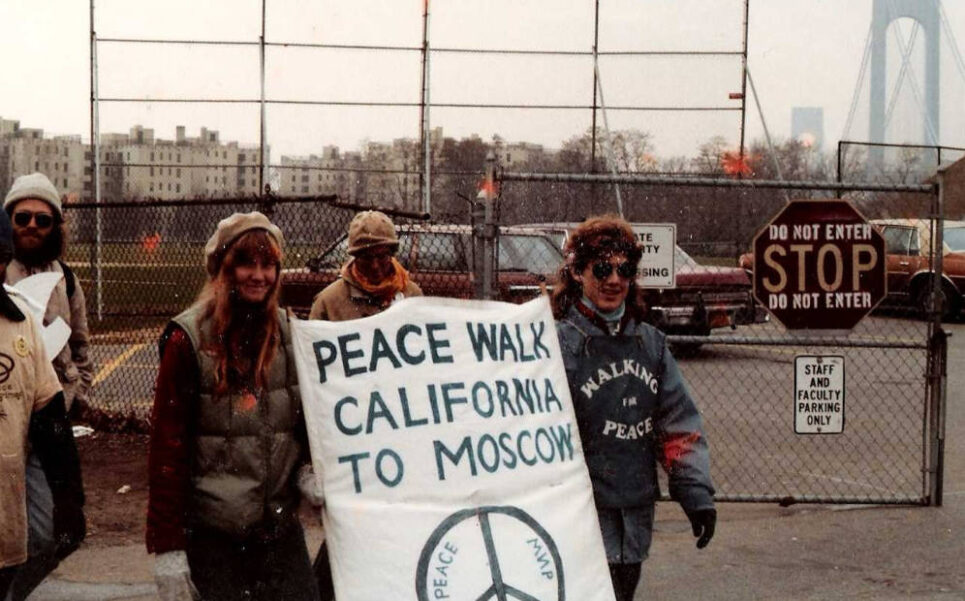

On November 1, 1961, at the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women brought together by Women Strike for Peace marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons. It was the largest national women’s peace protest of the 20th century.

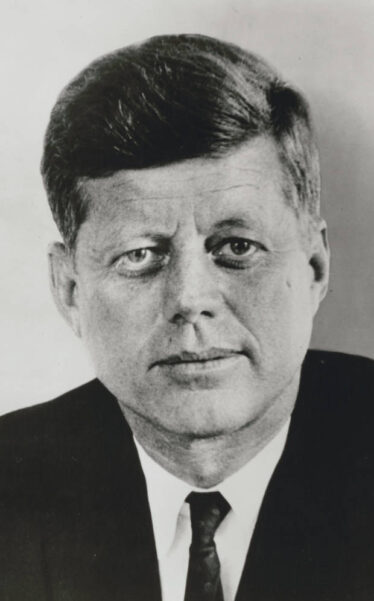

Public pressure and the research results subsequently led to a moratorium on above-ground nuclear weapons testing, followed by the Partial Test Ban Treaty, signed in 1963 by John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev.

In the 1980s, a movement for nuclear disarmament again gained strength in light of the weapons build-up and statements of US President Ronald Reagan.

On June 3, 1981, William Thomas launched the White House Peace Vigil in Washington, D.C.[28] He was later joined on the vigil by anti-nuclear activists Concepcion Picciotto and Ellen Benjamin.

On June 12, 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City’s Central Park against nuclear weapons and for an end to the cold war arms race. It was the largest anti-nuclear protest and the largest political demonstration in American history.

On May 1, 2005, 40,000 anti-nuclear/anti-war protesters marched past the United Nations in New York, 60 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In 2008, 2009, and 2010, there have been protests about, and campaigns against, several new nuclear reactor proposals in the United States.

The nuclear problem

Yet, today around 12,705 nuclear weapons remain. Countries possessing such weapons have well-funded, long-term plans to modernize their nuclear arsenals. More than half of the world’s population still lives in countries that either have such weapons or are members of nuclear alliances.

While the number of deployed nuclear weapons has appreciably declined since the height of the Cold War, not one nuclear weapon has been physically destroyed under a treaty. In addition, no nuclear disarmament negotiations are currently underway.

Meanwhile, the doctrine of nuclear deterrence persists as an element in the security policies of all possessor states and many of their allies. The international arms-control framework that contributed to international security since the Cold War, acted as a brake on the use of nuclear weapons and advanced nuclear disarmament, has come under increasing strain.

On 2 August 2019, the United States’ withdrawal spelled the end of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, through which the United States and the Russian Federation had previously committed to eliminating an entire class of nuclear missiles.

On the other hand, the extension of the Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms until February 2026 has been welcomed by Member States and the Secretary-General of the United Nations. This extension provides an opportunity for the possessors of the two largest nuclear arsenals to agree to further arms control measures.

Another pressing issue is that the nuclear problem poses an environmental issue, a large one. Scientists have stated that nuclear weapons pose the single biggest threat to the Earth’s environment.

Richard Turco (an American atmospheric scientist) of UCLA assured that detonating between 50 and 100 bombs would throw enough soot into the atmosphere to create climactic anomalies unprecedented in human history.

Tens of millions of people would die, global temperatures would crash and most of the world would be unable to grow crops for more than five years after a conflict.

In addition, the ozone layer, which protects the surface of the Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation, would be depleted by 40% over many inhabited areas and up to 70% at the poles.

A nuclear war could cause long-term damage to our planet. It could severely disrupt the earth’s ecosystem and reduce global temperatures, resulting in food shortages around the world.

Concluding

Nuclear weapons are the most terrifying weapon ever invented. No weapon is more destructive and there is no way to control how far the radioactive fallout will spread or how long the effects will last.

A nuclear bomb detonated in a city would immediately kill tens of thousands of people, thousands would suffer horrific injuries and later die from radiation exposure.

The very existence of nuclear weapons is a threat to future generations, and indeed to the survival of humanity.

What’s more, given the current regional and international tensions, the risk of nuclear weapons being used is extremely high. The nuclear-armed States are modernizing their arsenals, and their command and control systems are becoming more vulnerable to cyber-attacks. There is plenty of cause for alarm about the danger we all face.