Police abuse in Colombia is a continuous, latent issue, which can be felt in the environment, while we eat breakfast, walk, talk and feel it in our veins. Unfortunately, this is a reality that is not new…. is a reality that is touching our fiber, breaking our bones, and breaking our souls.

Many learned of the Ordoñez case

Although it is not a new situation, many people became aware of the Javier Ordoñez case. And, this is what happened: Javier Ordoñez died after being subdued and beaten by police in Colombia.

But how do we know these events happened? Well, there is a video of 2 minutes and 18 seconds in which it is clearly seen how two policemen keep Ordóñez subdued and apply several electric shocks while the detainee asks to be released on the ground.

He is beaten and pressed to the ground. In the video, Ordóñez can be heard shouting, asking the agents to please stop the aggression, while about nine Taser shocks are heard.

Sometime later, Ordoñez is taken to a police unit and then to a hospital in the west of the capital. Minutes later, he died.

These horrific images circulated on social networks and in local media, mobilizing thousands of demonstrators to protest against police abuse.

The indignation of thousands of people in the country was felt. They turned into acts of violence in which seven people died from gunshot wounds.

“Please stop, I’m begging you officer… please stop ”.- Javier Ordoñez –

The mayor of Bogotá, Claudia Lopez, condemned the police abuse but also that of the protesters.

Beyond the protests and the indignation of the citizenry at the death of Ordóñez, the mayor of Bogotá, Claudia López, and the prosecutor Francisco Barbosa condemned the event and announced investigations and reforms.

The rejection

But the case of Ordóñez, who was allegedly in breach of one of the quarantine restrictions, is the result of police culture and a corrupt system that rewards acts of abuse of authority.

Precisely in order to try to understand a little more about this, we decided to talk to different people. One of them is Tatiana Londoño, who is a lawyer with a Masters in International Law from Georgetown University and works constantly with issues of Public International Law, Human Rights, International Humanitarian Law, International Criminal Law, among others. We were also able to establish contact with Alejandro Lanz of the organization Temblores.

Laura Viera Abadía: Why was so much indignation generated by the case of Javier Ordóñez?

Tatiana Londoño: In the case of Javier Ordóñez, the fact is that people were able to witness the event from their computers and saw, it seems to me, without knowing the evidence, a clear case of police abuse of force, so much so that it caused the death of the citizen due to the rupture of one of his kidneys from a blow received… which is clearly an abuse of force. He could have been doing something that would not have been legal or that would have led to his detention but his detention does not imply a beating similar to that. So, that’s what generated the outrage… that people could see it on a video through their computer, and I think that’s what made that case so different. There have always been these terrible cases of police abuse, what happens is that now we can see them.

Laura Viera Abadía: It sounds terrible, but I think it is important that we talk about these events in figures because it seems that this is the only way people are impacted.

Alejandro Lanz, Temblores organization: There are 639 homicides committed during the last 3 years by members of the security forces. There are 40,480 cases of physical violence and 248 cases of sexual violence. It is something that worries us very much because it shows a very strong systematization within the institutionality against young people, LGBT, peasants, and also against certain social groups. Not a single person has been convicted for these crimes yet.

Laura Viera Abadía: What kind of problem do we Colombians have with the police?

Alejandro Lanz, Temblores organization: Clearly, as you are stating, this is not a new problem. It is a systematic problem that has been going on for a long time and it is a problem that affects certain groups of society in a differentiated manner.

Laura Viera Abadía: Hello Tatiana, please tell me exactly what is the problem of police abuse in our country?

Tatiana Londoño: I believe that the issue of police abuse has always existed in Colombia as well as in the whole world. It is people who have possession of weapons and have the possibility to use force. Before they did not know each other but today every person has access from their living room, from their computer and clearly they are shocked by what is happening. So, I do not believe that in Colombia there is police abuse. I believe that the police institution is very respected in general terms and has strict respect for human rights, but obviously, there are cases of people who abuse the force, there are police officers of police officers and as in any human organization there are good people and bad people.

Laura Viera Abadía: So, how do you see this?

Tatiana Londoño: Let’s say there are good people and bad people. There are people who are respectful of institutions and human rights and there are people who are not. The idea is to be able to find these people who are not and to be able to punish them appropriately, according to the law. So the issue is that these cases of police abuse that have occurred both in Colombia and in the rest of the world, it is much easier to make them evident, presenting a very good tool so that through pressure and citizen control, they can be prosecuted and justice can be done in these cases that were previously ignored, they were not known and in many cases there was impunity.

There are 11 homicides that occurred in the country, mainly of young people who were killed by the police. Five of them were killed as a result of violating some sanitary measures.

The rejection by the citizens left Bogota and has reached several other cities in the country. Some say that the protests are a reflection of not putting up with a situation that is by no means new in our country.

Laura Viera Abadía: Why did people come out with the case of Javier Ordóñez, what made society so indignant?

Alejandro Lanz, Temblores organization:There are several factors. One is the severity and lethality of public violence through this taser weapon. Let’s say that two members of the security forces attack his body on the ground.

He is neutralized and asks not to continue electrocuting him, there is another person who is recording it and they don’t seem to care. All this generated great indignation among the people but also something happened and that is that this boy was a middle-class boy and that also moved people, the place where the events took place and the socioeconomic characteristics generated a great impact and indignation both by the media and by the citizens in general.

Laura Viera Abadía: What has this particular case shown?

Alejandro Lanz, Temblores organization: It has shown the whole structural problem because this is a case where the police tried to hide the evidence, erase the reports, and despite the fact that it was being recorded they did not care.

Laura Viera Abadía: If we have the recordings and forensic medicine said that he died because of blows to the head and the rupture in the liver, why is there no legal consequence? In Colombia, someone steals a loaf of bread and they go to jail. but there is a video in which a person is killed, in which there is the forensic medicine report, and beyond the indignation, beyond what happened in the CAI, beyond the fact that people went out, beyond all this social movement, there are no legal consequences… What is happening?

Alejandro Lanz, Temblores organization: Yes, of course, that is one of the problems. this specific case, which was achieved due to media pressure, is that the case will not go to the military criminal justice and will remain in the ordinary justice system. and that is one of the problems of the system. because the cases that are committed by the public forces and specifically by the police most of the time end up being studied by a military criminal justice system that is a justice system attached to the ministry of defense and whose judges are appointed by the executive and this is part of the structural problem because there is no difference between the police and the armed forces.

End of 2019

Since November 21, 2019, thousands of Colombians have taken to the streets as part of the national strike to protest issues ranging from tax reform proposals to the murder of human rights defenders.

It is a systematic problem that has been going on for some time and is a problem that affects certain groups in society in a differentiated manner.

Most of the protests were peaceful, but some demonstrators committed acts of violence, including stone-throwing at police, looting, and burning of public and private property, especially in Bogotá and Cali. In several cases, police used excessive force against protesters, including beatings and improper use of “less-lethal” weapons during anti-riot operations.

On January 22, prosecutor Espitia told Human Rights Watch that his institution was investigating 72 cases of possible abuses by police during the protests. However, no one had been charged.

The Ministry of Defense indicated that the military criminal justice system was investigating 32 cases of possible abuses related to the protests. It should be noted that, according to international human rights law, abuses attributable to security agents should be investigated by the ordinary criminal justice system, not the military criminal justice system.

There are 11 homicides that occurred in the country, mainly of young people who were killed by the police. Five of them were killed as a consequence of violating some sanitary measures.

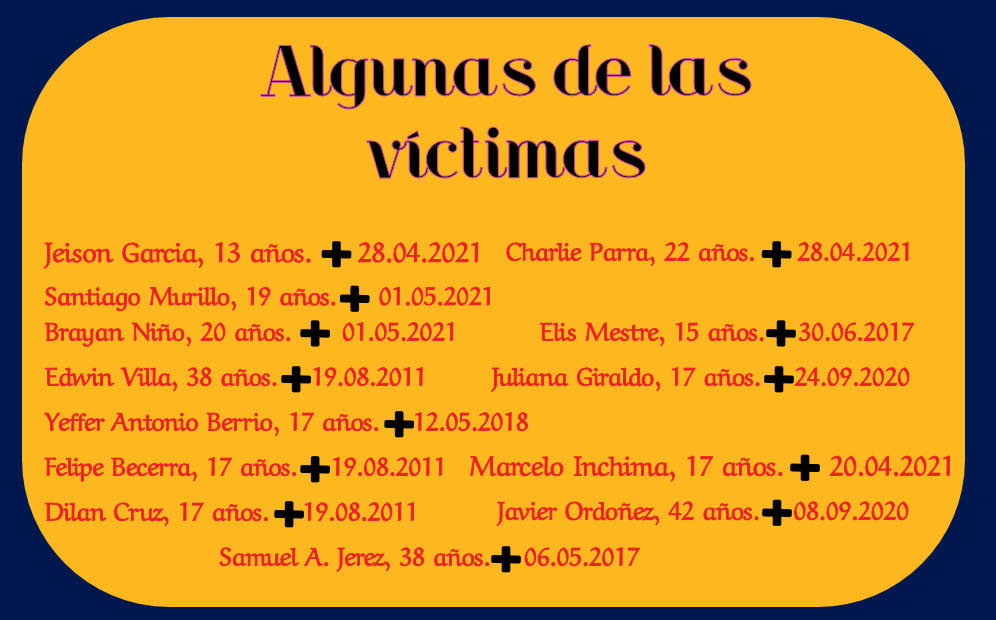

Some cases

One of the cases that generated the most impression occurred on November 23, 2019, while 17-year-old Dilan Cruz was protesting. He was hit by a handmade projectile fired by the captain of the Mobile Anti-Riot Squad, ESMAD, Manuel Cubillos Rodriguez.

Dilan was hit in the head with a bean bag, which is a bag containing multiple pellets. Two days later, the young student died, triggering a strong rejection of the police actions by the citizens.

There are many witnesses to his death and it was captured on video, from different angles, and it took place just when the Esmad was dispersing the marches that were trying to reach the center of Bogota.

The recordings show how Cruz ran with other demonstrators to avoid the stun grenades and tear gas. Also how he picked up two of them to throw them back. The footage shows how a riot police officer fired directly at the young man.

Cruz collapsed on 19th Street and 4th Street. The projectile embedded itself in the back of his head, leaving him unconscious. Since then and after his death, Dilan Cruz has become a symbol of the protests that have been taking place throughout the country since November 21.

In an attempt to cover their backs, somehow, a smear campaign began to be generated in which different versions of Dilan began to circulate on social networks, where he was accused of inappropriate behavior. However, both classmates and teachers denied such versions.

Laura Viera Abadía: Tatiana, let’s talk a little about Dilan Cruz’s situation. What happened?

Tatiana Londoño: The authorities should look to see if in this case there was malice or not. There is a very clear difference between wanting to cause injuries to someone and causing their death and a case of control of demonstrations that have become violent, with weapons that are allowed, and that may have caused the death when they were trying to control the demonstration. This is an issue that the authorities should look into and study. See if the ESMAD agent who shot wanted to cause death and that is why he shot him or if he wanted to cause serious injuries beyond the protocols that they have established for the use of force, or if those protocols for the use of force in violent demonstrations go a little further and generate this type of risk of human rights violations and that can cause death and that can cause death.

Laura Viera Abadía: Then, how should we proceed legally?

Tatiana Londoño: I do not believe that this is an investigation that should be done lightly. It is an in-depth issue regarding the police handling of the demonstrations. So, it is an issue that the authorities have to look into. I do not believe that in the months that we are going, with the speed with which the Colombian judicial system is advancing, that we would all like to have a decision in a month, unfortunately, it takes longer. Much more in times of pandemic when the courts were suspended and closed for several months.

Laura Viera Abadía: Tatiana, is there anything else you would like to add on the issue of impunity?

Tatiana Londoño: Yes, the fact that there is no punishment does not mean that there is impunity. We must remember that the agent also has human rights and the right to due process as we all have.

Another case that shocked the country was that of the young graffiti artist Felipe Becerra, murdered on August 17, 2011.

He died after being shot in the back from the sidearm of Bogotá Metropolitan Police patrolman Wilmer Antonio Alarcón, who was sentenced to 37 years and six months in prison and remains a fugitive from justice.

Diego Felipe was 16 years old at the time and was painting graffiti in the company of two friends in the northwest of Bogota and they were detected by the uniformed police officer.

At the time of his death, some uniformed officers wanted to tarnish his name by saying that he was an alleged mugger. Investigations showed that the minor was simply painting graffiti and that he was attacked when he was defenseless.

Laura Viera Abadía: Is there impunity in the case of Felipe Becerra?

Tatiana Londoño: In the case of Felipe Becerra, there was no impunity. The police patrolman who did it was sentenced to 37 years. And of course, he remains a fugitive from justice, so I do not think that we are on the platform of police abuse and impunity in that case, but rather on the issue that here in Colombia and in many countries it is one thing to impose sentences and another is that if the person is not captured it is a bit difficult. So it is a matter of the functioning of our judicial system and of our police system to capture people and to strengthen that system.

Yes, the fact that there is no punishment does not mean that there is impunity. We must remember that the agent also has human rights and the right to due process as we all have.

On January 14, 2020, the Attorney General’s Office, an independent body, asked the National Police to suspend the use of 12-gauge shotguns that were used when Cruz died.

The Attorney General’s Office said police officers receive little training in the use of this weapon, often by officers who are also untrained in its use.

On the morning of November 22, when 20-year-old Natalia Gema Racero was on her way to work, she was unable to make it because of the demonstrations, as there was no transportation and she had to return home. On the way, she saw the police firing tear gas canisters at the demonstrators, so she ran away along with other people. Six officers held her down and told her they were detaining her for her “protection”.

The police took her inside a Transmilenio station, where an officer touched her breasts twice to see if she was hiding anything. Police officers then locked her in a room with other detainees.

Two hours later, they put her in a van, she said, beat her on the head and back with a baton, and told her to sing so they would not beat her. She was taken to the Kennedy police station, where two hours later, the authorities released her.

Laura Viera Abadía: What has happened to police officers who have committed abuses of force or homicides against people in the country?

Alejandro Lanz, Temblores organization: Well, we have seen that of the cases we have seen that two high school graduates have been removed from their posts. The rest, the investigations are going on while they are still in office. But, the only two that we have been able to get removed from office are the two high school graduates who tortured a young man by burning his hair.

Laura Viera Abadía: Yes, I saw that and it was horrible! it made me want to vomit. it’s disgusting to see how they burn her hair. what right do they have to do that? they think they are untouchable.

Alejandro Lanz, Temblores organization: It’s terrible.

Laura Viera Abadía: They only suspend them, don’t they put them in jail?

Alejandro Lanz, Temblores organization: They suspend them while they conduct an active investigation into their behavior, but they have been very diligent in suspending and removing police officers who do not follow authority.

Laura Viera Abadía: But that is absurd

Alejandro Lanz, Temblores organization: Totally absurd but they are very diligent in suspending when the chain of command is broken, but we do not see the same efficiency when a police officer is implicated in acts of violence.

On May 12th, 2018, a young Afro-descendant from Quibdó, Yeffer Antonio Berrio, died. He died after being searched without cause. During the search, one of the agents decided to draw his gun and shoot him.

Social Outrage

The public debate on the excessive use of force has taken center stage since the wave of protests against the government of Iván Duque that shook the country at the end of 2019.

Social protest over too many acts of police abuse has been held back by a country quarantined by Covid 19, reports of continued police aggressions continued to be recorded throughout 2020.

No one can forget how police officers attacked a senior citizen informal vendor. Also when several trans women denounced that in the early morning of June 20 in Bogota, agents beat them and shot them with pellets.

In July 2020, a video was released showing a man on the ground with his face covered in blood while police auxiliaries tried to set him on fire.

Obviously, social outrage among all is to be expected. Let’s keep in mind that from 2017 to 2019, the Legal Medicine Institute recorded 639 homicides committed by law enforcement agencies in Colombia. From these figures, it is possible to determine that allegedly 328 cases were committed by the military forces, 289 by the police and 22 by the intelligence services.

The department that presented the highest number of homicides between 2017 and 2019 was Antioquia. It was followed by the departments of Atlántico and Bolivar. Bogota is in fourth place in terms of the number of murders.

International, Regional Law, and Human Rights Watch

According to the norms of international and regional law, cases of human rights violations should not be tried by military tribunals. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights has determined that “the military criminal jurisdiction is not the competent jurisdiction to investigate and, where appropriate, try and punish the perpetrators of human rights violations”.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has determined that it is not appropriate to try human rights violations in military jurisdictions because “when the State allows investigations to be conducted by the bodies potentially implicated, independence and impartiality are clearly compromised”.

Human Rights Watch, an international organization dedicated to the protection of human rights around the world, has been key in unmasking and highlighting this problem in Colombia.

To achieve this, between November 2019 and February 2020, Human Rights Watch interviewed victims of abuse, family members, human rights lawyers, and government officials; reviewed medical reports and criminal complaints.

The agency, Human Rights Watch, has evidenced several documents establishing that by the end of 2019 multiple cases of abuse against mostly peaceful demonstrators who participated in nationwide protests. However, progress in investigations against these officials has been very limited.

Laura Viera Abadía: Tatiana, how does the military criminal system work?

Tatiana Londoño: The military criminal justice system is designed to judge cases of abuses and crimes committed by members of the security forces, both military and police, in the exercise of their duties.

Laura Viera Abadía: Ok, but then… what exactly has happened?

Tatiana Londoño: For me, there is no doubt that the police officers who abused their force in demonstrations or in cases such as that of Ordonez, were in the exercise of their duties. They were not out on the street having a drink and got into a fight with someone in a bar. They were carrying out their duties as police officers and then they exceeded their duties and that is the competence of the military criminal police. The military criminal justice for several historical reasons, is the criminal judges are in the chain of command. That is to say, their superiors are still active and therefore they cannot strictly give them orders about the processes, but they can punish them by transferring them to less favorable places, etc. Therefore, the military criminal justice system has been known for not being very efficient. That is why they have sought, through arguments that seem to me to be valid, to take these types of politically significant processes to the ordinary justice system.

Laura Viera Abadía: Tatiana, but why do you think they should not go to the ordinary justice system?

Tatiana Londoño: Ordinary judges normally do not have a good grasp of the protocols that govern the actions of the military and public forces. That is why it would be ideal for the military criminal justice system to be efficient and effective in these processes because they are the ones who know very well what the protocol is in a protest, or what international humanitarian law is, how a military operation is carried out. Ordinary judges often do not know this and it can lend itself to cases of injustice, but due to their great historical inefficiency, these cases have been taken to the ordinary justice system.

But, let’s be as clear as possible because when we are trying to expose such a sensitive issue as police abuse we deserve as much information as possible.

Since November 21, 2019, thousands of Colombians took to the streets as part of a national strike to protest issues ranging from tax reform proposals to the murder of human rights defenders.

While the protests were generally peaceful, some demonstrators committed acts of violence, including stone-throwing at police officers, looting and burning of public and private property, especially in Bogotá and Cali. And, on several occasions, police used excessive force against protesters, including beatings and improper use of “less-lethal” weapons during anti-riot operations.

On April 28, thousands of people took to the streets in dozens of Colombian cities in protest against a tax reform bill. The government withdrew the proposal a few days later, but demonstrations continued over issues including economic inequality, police violence, unemployment, and lack of adequate public services.

Police have repeatedly dispersed peaceful demonstrations arbitrarily and used excessive and often brutal force, including the use of lethal ammunition.

Human Rights Watch has been able to confirm that 34 deaths occurred in the context of the protests, including those of two police officers, a judicial investigator, and 31 protesters or bystanders, at least 20 of whom appear to have been killed by police. Armed individuals in civilian clothes have also attacked protesters, resulting in the deaths of at least five of them.

Among the injured are journalists and human rights defenders who were covering the protests. Many of them were wearing vests identifying them as members of the press or human rights organizations.

Human Rights Watch obtained credible evidence indicating that police killed at least 16 protesters or bystanders with lethal ammunition fired from firearms. In the vast majority of these cases, the victims had gunshot wounds to vital organs, such as the chest or head, which judicial authorities told Human Rights Watch is consistent with intent to kill.

According to Ministry of Defense data, more than 1,100 protesters and bystanders have been injured since April 28, although the total number is likely higher, as many cases have not been reported to authorities.

On May 14, the Ombudsman’s Office reported that it had received complaints against members of the police for 2 cases of rape, 14 cases of sexual assault, and 71 other cases of gender-based violence, including slaps and verbal abuse.

Human Rights Watch also documented 17 violent beatings by police, in many cases with batons. One victim, 24-year-old Elvis Vivas, died in a hospital after being brutally beaten by police officers.

At least 419 people are reported to have disappeared during the protests. On June 4, 2021, the Prosecutor’s Office indicated that it had located 304 of those people. In some cases, those who reported them missing did not know that these people had been detained.

Misuse of weapons

One factor to take into account is the use of weapons. According to international human rights standards, the use of lethal weapons to disperse assemblies or demonstrations is always unlawful. Likewise, lethal weapons may only be used when strictly necessary to address an imminent risk to life or physical integrity.

Under Colombian law, police may use firearms in self-defense or to protect persons from “imminent danger of death or serious injury, or for the purpose of preventing the commission of a particularly serious crime that poses a serious threat to life.

It should be made clear that both the regular police and ESMAD indicated to HRW that they have not used lethal weapons during the demonstrations.

However, the human rights organization corroborated several videos in which police are seen firing firearms in the context of the demonstrations, in circumstances in which there did not appear to be a risk to a person’s life or physical integrity.

Tear gas canisters are supposed to be fired into the sky in order to slow down the trajectory of the projectiles, which are heavy so that after a downward arc they fall to the ground.

The police used tear gas on several occasions against peaceful demonstrators.

Police also appear to have fired tear gas with riot guns in a reckless and dangerous manner on several occasions.

The police also used multiple projectiles launching systems, known as Venom, which allows up to 30 rounds of tear gas, smoke, or stun rounds to be fired at a time.

In one incident on April 30, police were attempting to disperse protesters blocking a major Cali road. A video records the moment when an officer approaches a protester with a shield.

The police officer kicks the person and then throws what appears to be a gas can or some other “less-lethal” type of ammunition, directly at point-blank range.

From close range, any such ammunition can cause serious damage or kill. According to reports, on the same day, another protester was killed when hit by a tear gas canister, just a few meters away.

In another case on May 18 in Bogotá, Esmad officers can be seen firing tear gas at volunteer paramedics assisting an injured protester.

Attacks on detainees

Police violence ranged from beating protesters already in custody with truncheons to shooting a 17-year-old student who was running in the head, with fatal consequences.

In several videos, police officers can be seen punching and kicking people who are in custody and do not appear to pose a threat.

On May 1, three days into the strike, police dispersed a group of people in the western city of Pereira.

The video shows the moment in which the demonstrators flee. Two of them try to hide, but the officers quickly locate them. The officer also appears to mock the protesters by raising his fist in the air and repeating a popular protest slogan. Said officer then slams one of the protesters into a window that shatters.

Among the dozens of people who have been recorded as dead since late April, the government said at least 17 protesters had died in direct connection with the protests and the police response.

Obviously, these cases are not always recorded on video, which makes the events that occurred difficult to prove and establish the exact role played by officers in these deaths.

But the case of Marcelo Agredo Inchima, a 17-year-old high school student on April 28, is clearer: a police officer shot him in the head while he was running. You can see the moment when Agredo Inchima kicks a police officer who is on a motorcycle. As he runs away and is no longer a threat, the officer unloads at least three shots, one of which hits Agredo Inchima, who collapses.

Abusing the power of force

The police are the government’s preferred resource to achieve many objectives.

Last Thursday, September 24, life changed the lives of two families in the south of the country. At a checkpoint on the road to Guatemala, in Miranda (Cauca), a shot fired by a soldier of the National Army ended in the head of Juliana Giraldo, who died instantly on the spot.

Juliana Giraldo, a 36-year-old trans woman, was a hairdresser. She had been living in Miranda for two years with her boyfriend, Francisco Larrañaga.

But what exactly happened?

Juliana Giraldo and her boyfriend Francisco Larrañaga decided to travel to the neighboring municipality of Corinto, just 15 minutes away, in the company of two other people to do some shopping.

Larrañaga said that she was driving through the Guatemala sidewalk when she saw some members of the Army and noticed that she had forgotten the papers of her vehicle, a white Mazda 626, so she chose to turn towards the house to avoid them.

Just as he was making the maneuver, two soldiers appeared from the bush, one of them shot at the white car in which they were traveling.

“They killed Juliana, that guy (military) shot her in the head. Please, help me”.- Francisco Larrañaga –

The aftermath was extremely painful. Larrañaga was running from one side to the other while Juliana was disgraced in the passenger seat of the vehicle.

This death, whose responsibility was assumed by the Army, was condemned by President Iván Duque, who ordered a speedy investigation of the facts. In addition to the loss of Juliana, which the family considers inexplicable, several issues about the procedure were brought to the attention of the Attorney General’s Office.

According to the army, they were making a checkpoint, a control post. But, there were no signs by the Army to identify the supposed checkpoint.

And, the truth is that when these procedures are carried out, the checkpoint should always be marked with fences, with at least 10 men in front and one person in command. In addition, the first step is to identify oneself and for “no reason to shoot”.

However, the soldier has assured that he shot the tires of the vehicle after seeing that they did not want to stop.

The case brings to the table, once again, the criticized excesses of the security forces in some of their procedures.

The Colombian police are under the Ministry of Defense and have often been deployed to fight armed groups together with the Armed Forces, which has meant that there is no clear separation of the different functions of these two forces.

In situations of armed conflict, the use of force is governed by international humanitarian law, and the rules are very different from those in civilian contexts, such as in protests.

Also, police involved in abuses are often tried in military courts, where there is little likelihood that officers will be held accountable for such abuses given their traditional opacity and lack of independence.

Colombia needs a civilian police force that is trained to respond to demonstrations in a manner respectful of human rights, and whose members are held accountable for abuses.

Laura Viera Abadía: In cases of police abuse against LGBTI people do you have different things in international law?

Tatiana Londoño: One of the essential postulates is the case that only the police, and no one else, can discriminate against these people and attack them for being LGBTI. This is one of the issues in terms of international law in the international treaties that state that no one can be discriminated against because of their sexual orientation. So, for example, if the police are carrying out raids or excessive use of force against LGBTI people, clearly this must be sanctioned as a very serious disciplinary offense and of course it can also have criminal implications.

Laura Viera Abadía: Tatiana, what do we need for military criminal justice to really work in our country?

Tatiana Londoño: I believe that the military criminal justice system must undergo several fundamental reforms so that it becomes a justice system that works. If not, cases will continue to be brought with the argument that if I committed a crime while I was not in the office, I will go to the ordinary justice system. That is the argument of Human Rights Watch and other platforms that have argued this and that argument has been bought by the Supreme Court of Justice and that is why many cases have been taken to the ordinary justice system.

Laura Viera Abadía: Tatiana, in international terms, can the International Court intervene or how are human rights abuses punished?

Tatiana Londoño:: The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights can only intervene when all domestic instances have been exhausted.

Laura Viera Abadía: Could you explain to me what that means?

Tatiana Londoño: That is, when there was flagrant impunity when the internal justice system did nothing at that time, the families could go before the Commission but not to punish the perpetrators. That is not within the competence of the IACHR. The IACHR only looks at the responsibility of the State in terms of respecting the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. So, the families can ask the IACHR to sanction the State for these human rights violations, one of which is impunity, the lack of access to justice or the lack of prompt access to a judicial decision.

Concluding for the moment

During Colombia’s decades of conflict with violent rebel groups, the national police often fought on the front lines, with tanks and helicopters to combat guerrillas and destroy drug labs.

It was a force made for war, one that has now found a new front, on the streets of Colombian cities, where police have been accused of treating civilian protesters as battlefield enemies.

Laura Viera Abadía: Tatiana, what should we do to change these abuses, this behavior?

Tatiana Londoño: What I told you, the use of the networks to denounce abuse is a very valuable issue. also because in the attorney general’s office the police officers should have a camera because sometimes they only record the part in which the police officer is reacting and not when he is being beaten beforehand. So that the agents have a video that records the entire operation so that the judges can see when there was a case of abuse of force but not use them as a political tool, which is often done.

There is a collective outcry of indignation over the actions of the country’s national police. It hurts to say it, to write about it, and even more so to admit it, but police, army, and ESMAD officers have beaten, detained, and killed people at different times in the country.

We cannot forget that we are all born free and equal in terms of rights and dignity. For this very reason, we should have empathy and use reasoning before acting. The fact that someone has a position that gives them “power” or “authority” does not excuse us from killing or diminishing someone else.

Many have committed serious abuses against people. The Colombian government should take urgent steps to protect human rights and initiate a thorough police reform to ensure that officers respect the right to peaceful assembly and that those responsible for abuses are brought to justice. They are not protecting us, they are killing us.